A common misconception about effective teamwork is that it results from the directive of an authoritative leader, that is, a singular person or entity empowered to assign tasks and establish norms. However, research and personal experience show that consistently successful teams require a flexible leader willing to assume a variety of roles such as empathizer, observer, scientist, and even follower. In fact, as this article will discuss, often solutions to dysfunctional team dynamics come from insights gained from group members and/or self-reflection.

A key, evidence-based tool for identifying the factors preventing a group from “clicking” involves the use of mental models. A mental model is a version of reality that an individual creates in their mind; it is an individual’s perspective or view of the “truth” of a situation. Mental models enable a leader or team member to tune into the motivations, barriers, and emotions within the context of an event, and ultimately provide insight on how to intervene to improve a challenging dynamic. While an infinite number of frameworks exist, this article will highlight a few salient ones: technical versus adaptive challenges, the balcony versus the floor, and the self-awareness quadrant.

Technical Problems Versus Adaptive Challenges

Working through a turbulent period within a team necessitates an understanding of the difference between a technical problem and an adaptive challenge. Easy to pinpoint, technical problems tend to have quick fixes. Group members are generally receptive to solutions, and the specific implementation of the solution can be delegated by an authority or expert. Adaptive challenges, in contrast, can be difficult to uncover and solutions may not exist. Instead, these issues become conflicts that must be managed. Addressing these obstacles requires significant effort from all parties, and may necessitate changes in values, beliefs, roles, and relationships.

Take, for example, a soccer team with a lack of camaraderie and low morale. The coach might mandate that players wear uniforms every day and participate in team bonding activities in order to improve team cohesion. This simplified, structured response may improve the situation if the low morale results from a technical problem such as a new team with members that do not know each other well due to lack of time together. However, this approach may prove ineffective for an adaptive challenge such as strained relationships between teammates attributed to a perceived unfair allocation of playing time.

The Balcony Versus the Dance Floor

The first step in addressing adaptive challenges requires individuals to remove themselves from the trenches or “dance floor” in order to gain a broader perspective of the situation from the “balcony.” In doing so, the group’s dynamics can be studied as a “system” with human and non-human elements. Ideally, this vantage point enables the observer to more objectively analyze the situation and uncover obstacles affecting the group.

Returning to the soccer team example, there are a plethora of questions to explore: What affects each person’s morale? How do they view their relationships with their teammates and their coach? How do non-human elements such as time spent together, access to the playing field, weather, etc. impact the dynamic?

The Self-Awareness Quadrant

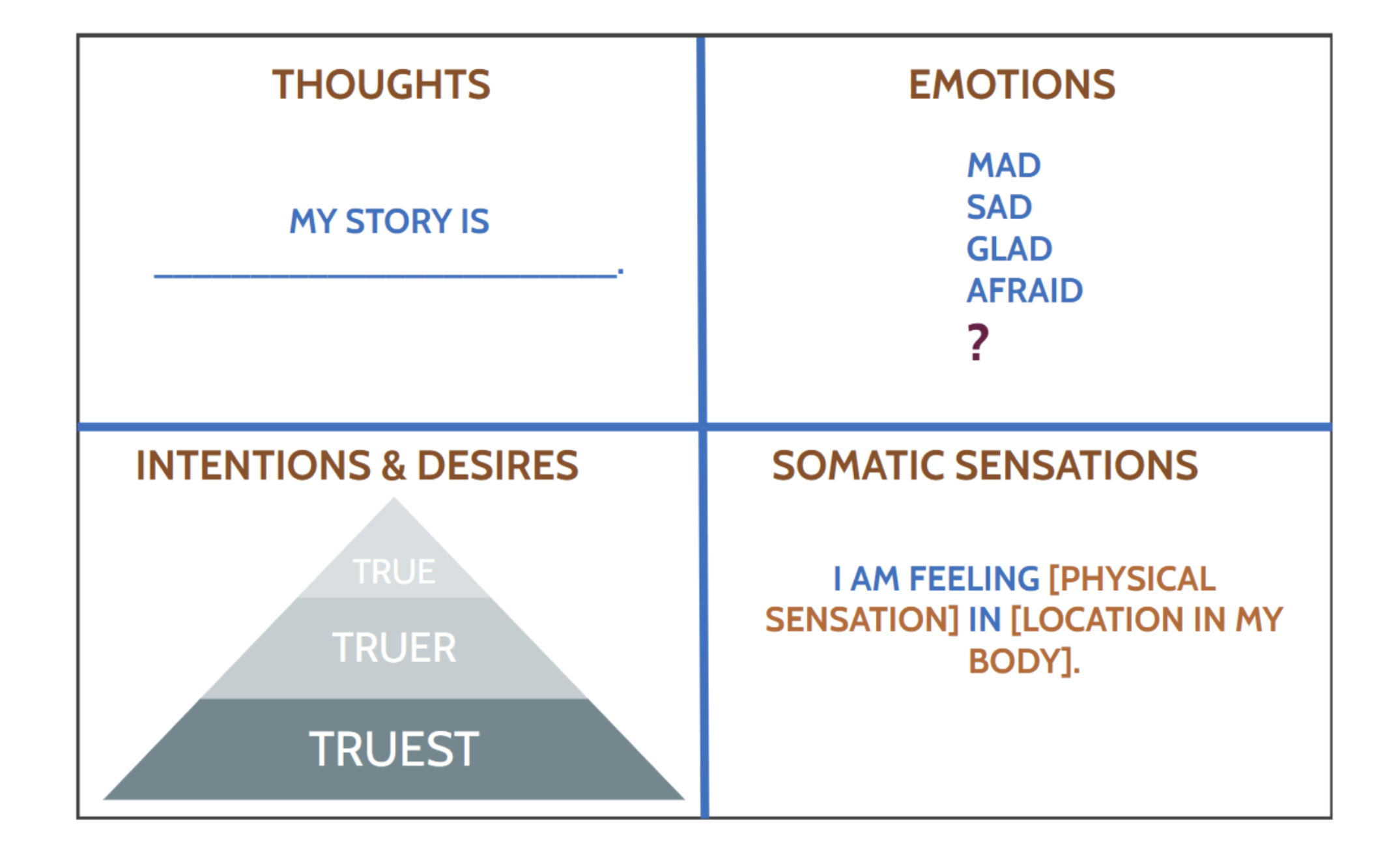

An analysis of the human elements of a system involves not only a study of others but also of oneself. A mental model applicable to the self, the self-awareness quadrant, utilizes a multi-step approach to systematically identify one’s personal contribution to the team dynamic.

First, one must identify the story they tell themselves by asking the question, “How do I approach this scenario?” One might believe that “My teammates and I do not get enough playing time during games.” After identifying their narrative, the person must then describe what emotions accompany this belief. A standardized approach incorporates four basic emotions (mad, sad, glad, and afraid) to hone in on the discomfort as well as the desired change. One might admit that “Spending time on the bench during games causes me to feel mad and sad, and I wish I had an opportunity to play more.”

The next phase involves being honest with oneself. A person’s intentions or desires frequently boil down to three core questions: am I good, am I loved, and am I competent? To determine which of these beliefs is threatened, apply the “true-truer-truest” model. At the “true” level lies a statement that one would share with other people. It often has a sense of nobility and focuses on the group (“Spending time on the bench makes my teammates feel mad and sad”). Delving deeper, the “truer” statement possesses a more selfish quality and focuses on one’s desires (“I do not get enough playtime and that frustrates me”). Finally, the “truest” statement reflects the purpose of the initial questions regarding feelings (“I am not given enough playtime because I am not competent”).

As the graphic below shows (the so-called “self-awareness quadrant”), attaching a somatic sensation to one’s feelings further enhances one’s understanding of their genuine emotions and motivations. For example, the anger that may accompany a lack of competency may cause sensations such as flushing of the face or discomfort in the chest.

Conclusion

This brief overview of the psychosocial tools behind effective team building illustrates how scientific models influence this practice and ultimately the strength of a team. As our world and innovation depend more and more on collaboration, these skills become increasingly relevant and crucial aspects of one’s toolbox. This holds true regardless of whether a person serves as a leader or group member. Finally, the application of these tools is far-reaching, and includes everything from professional or educational environments, to situations among one’s friends or family members.

References

Barrett, L. F. (2017). How Emotions are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Heifetz, R. A., Grashow, A., & Linsky, M. (2009). The Practice of Adaptive Leadership: Tools and Tactics for Changing your Organization and the World. Harvard Business Press.

Leadership Institute of Seattle of Saybrook University. (n.d.). Collaboration in Times of Intensity. Saybrook University.

Leave a comment