An unhappy but common theme in the post-pandemic years has been burnout. Many terms have been echoed to describe this phenomenon, such as the recent trend of “quiet-quitting” or the pervasive “senioritis,” which manifests about this time of year. While burnout is not a clinical condition nor a disorder, its serious effects of listlessness and unproductivity have led the WHO to classify it as an “occupational phenomenon” in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11). Recent surveys have found that somewhere from one-half to two-thirds of U.S. employees have experienced some form of burnout and that this stress hinders their ability to concentrate and perform optimally. The effects may be worse among certain populations—for instance, according to a 2022 report by the CDC, burnout was regularly reported among 46% of healthcare workers. Limited resources, tenuous situations, and workplace injustices can contribute to this motivational plight. However, at other times people may feel unmotivated for no apparent reason. In light of this, the psychology of motivation is highly relevant not just to individuals but also to policymakers seeking to maximize well-being and efficiency.

The goal of this article is to introduce several key theories of Motivation Psychology to contextualize burnout. These theories explain the “why” behind behavior by calling upon diverse psychological perspectives. For instance, while evolutionary psychologists have formulated one theory for motivation based on instincts, social psychologists have focused on surrounding pressures and come up with an entirely different picture. Together, these theories complement each other in the search to understand the underlying forces that shape our behaviors. Each theory also provides unique perspectives on harnessing motivation and reducing burnout in schools, workplaces, and everyday life.

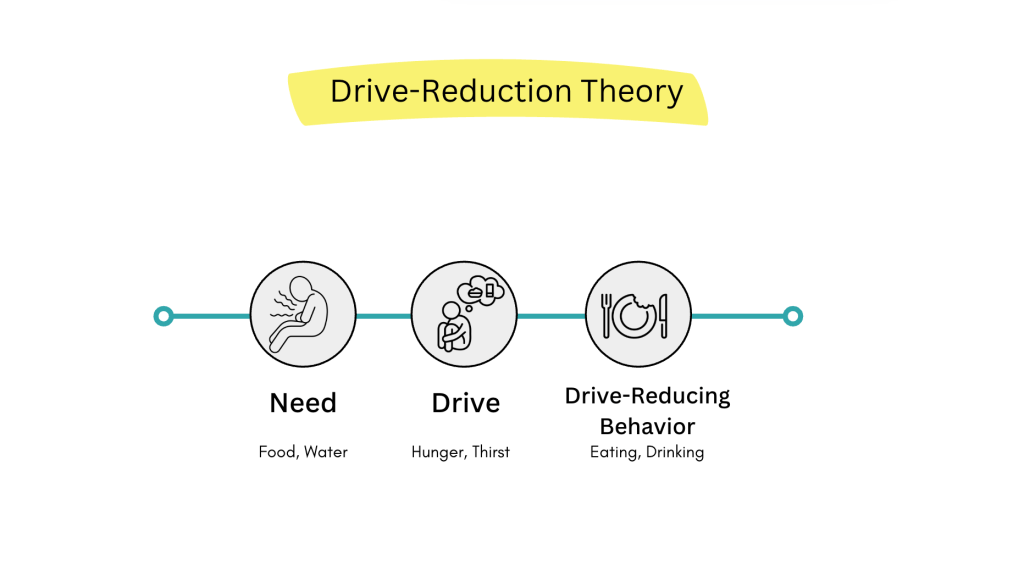

1. Drive-Reduction Theory

As one of the foundational theories of Motivation Psychology, Clark Hull’s Drive-Reduction Theory explains that behaviors are initiated in order to satisfy physiological needs. This applies primarily to physical, rather than mental, drives such as buying lunch to reduce hunger or drinking water to quench thirst. While drive-reduction theory does not explicitly apply to burnout—which is usually a mental state—what is notable is that individuals experiencing burnout tend to experience deficits in meeting these physiological needs. This suggests that for sleep-deprived residents working long shifts in the hospital or busy workers scrambling to skip lunch, other motivations interfere with this innate drive to satisfy physiological needs. When these needs—sleep, food, water—aren’t met and homeostasis isn’t achieved, people’s risk for burnout and negative health outcomes rises.

2. Incentive Theory

Building on Drive-Reduction Theory, Incentive Theory posits that our behaviors are motivated by external, rather than internal, rewards. Societal forces like reinforcements and punishments elucidate certain behaviors and fundamentally drive the ways we act; indeed, this theory was created by B.F. Skinner and largely echoes Behaviorism. Much of burnout can be explained by people’s motivation coming from external incentives which subsequently lose their luster, leading people to question their sense of purpose. The corporate world revolves around incentives—most people only work monotonous desk jobs to receive a paycheck, a promotion, or more days off. Similarly, students may only work tirelessly to achieve a report card grade, or athletes may only try hard in practice to clinch a trophy or avoid having to run sprints. Incentives are a reasonable, logical source of motivation—a scientist may spend late nights in her lab to secure grant funding, or a salesman might entertain customers to get a commission. When making big choices, being cognizant of the powerful incentives motivating our behavior, and how these interact with our priorities, is vital. Burnout can ensue when people strive hard to achieve incentives while sacrificing their personal needs. At other times, employees may feel burnt out if they work hard to advance, but find that the promised incentives are not satisfactory enough. Institutions like schools can create a healthier sense of motivation by re-evaluating the incentives that they provide.

3. Achievement Motivation

Similar to Incentive Theory, Achievement Motivation Theory states that people’s behavior is guided by a strong desire to achieve a sense of control, importance, and mastery. However, Achievement Motivation crucially differs in that it can be derived intrinsically or extrinsically. In general, intrinsic motivation, which comes from within, easily outpaces extrinsic motivation like money or fame. Having a genuine interest in something is crucial to maintaining a high work rate and avoiding eventual burnout. Motivation should come not from looking for external “pulls,” but by focusing on small, personal goals to master a task or triumph over small accomplishments. Try to find an innate desire to accomplish something—practice an instrument because it’s intrinsically rewarding, read a book that you enjoy—and harness this motivation throughout other contexts of life. Schools and companies can also motivate people by creating new goals and tasks for people to achieve, thus avoiding the drop in motivation that comes with dull or unchallenging work work.

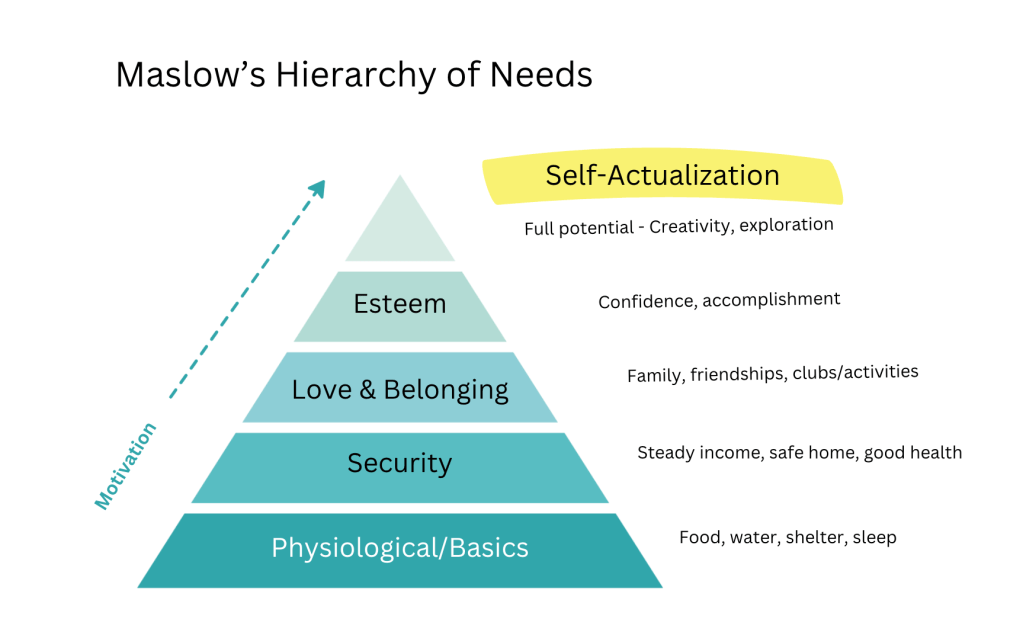

4. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, which was developed in 1943 by Abraham Maslow, ranks desires into five tiers—physiological needs, safety, belonging, esteem, and self-actualization—which people strive to fulfill. According to Maslow, people must first satisfy the basic needs of food, shelter, and water, before they can seek a sense of safety, which—in turn—predates a craving for a feeling of belonging and love. Only after we feel loved by others can we then seek to achieve a sense of self-esteem and ultimately self-actualize, or become the fullest versions of ourselves. Maslow’s Humanistic perspective was that people could not move onto achieving a different stage of desires without fulfilling the prior stage. For instance, someone who only focus on the achievement of the Esteem stage but neglects to forge lasting relationships or fulfill physiological needs like adequate sleep has less of a stable psychological foundation and may be at greater risk for burnout. Motivation-wise, this hierarchy is central to understanding why people are motivated to constantly seek different desires throughout life. Maslow and other humanists argued that the central, underlying motivation of life was to achieve self-actualization and be able to creatively and authentically express oneself. This constant drive to feel like we are valued by others (belonging), to feel confident and unique (self-esteem), and to finally feel like we’ve meaningfully contributed (self-actualization) can explain the relentless drive that results in burnout. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs can also explain how, if people’s career or life choices are not helping them advance to the next stage and achieve self-actualization, a feeling of burnout and stagnation can ensue. To increase motivation, the solution may be to turn away from external incentives and shallow achievements, and instead forge a path toward self-actualization.

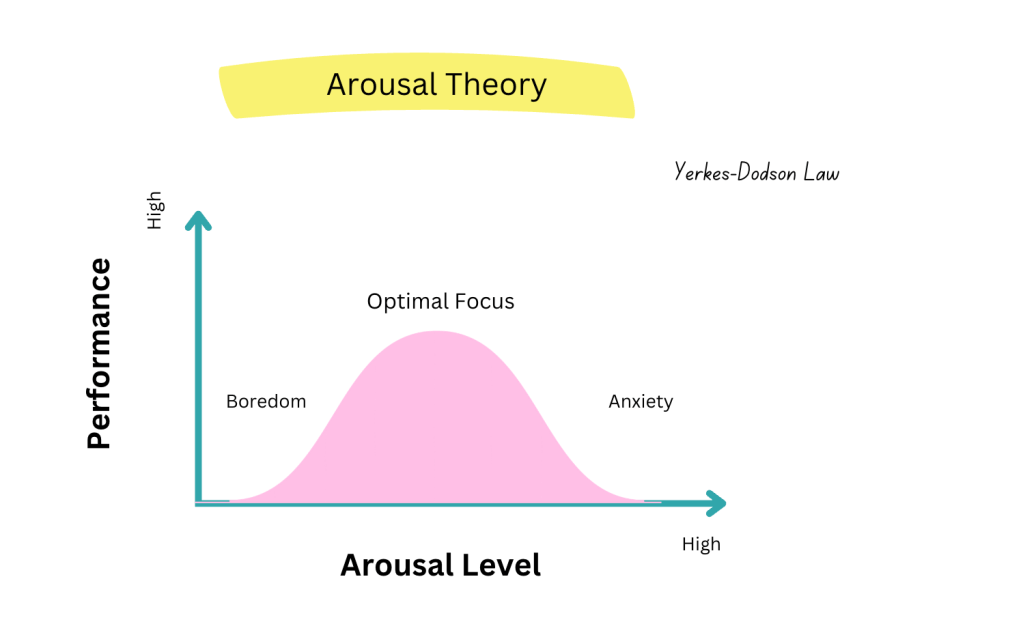

5. Arousal Theory of Motivation

According to Arousal Theory, which was first proposed in 1938 by Harvard professor Henry Murray, people’s actions are driven by a desire to maintain optimal arousal; that is, to relieve boredom in times of under-stimulation or decrease tension from high arousal. In answer to the question, “Why do people act in the first place?” this theory proposes that people initiate new activities like jogging, picking a fight, or starting a business to satisfy a need to be sufficiently stimulated. People mow the lawn on Sunday afternoons to feel like they’re doing something or go skydiving just for the thrill of it. On the other hand, if people are experiencing too much arousal, they may watch TV on weekday nights, read a book, or take a nap. While increased arousal and adrenaline are beneficial up to a certain point, according to the Yerkes-Dodson Law, too much arousal can lead to impaired performance. Burnout, especially, seems to be characterized by perpetually elevated arousal levels while one works, leading to increased tension and worsened capabilities. To deliberately lower arousal, try taking breaks at work to listen to calming music, make small talk with a colleague, or pause to mentally reset. If assignments or emails become overwhelming and arousal is consistently too high, it is no surprise that people will eventually reach a tipping point where energy is depleted and there is a strong urge to slow down or stop. On the other hand, monotonous tasks with too little arousal can lead to a lack of motivation and burnout, thus, fostering school and workplace environments with a balance of intellectual stimulation and arousal is key.

6. Cognitive Dissonance Theory

Lastly, Cognitive Dissonance Theory, a tenet of Social Psychology, can also function as a strong underlying force of motivation. This theory explains that people strive to be consistent in their attitudes and behaviors, and when a person simultaneously believes one thing but acts in a way that is incompatible with that belief, a state of internal tension arises. Cognitive Dissonance Theory explains, for example, how a smoker who knows that cigarettes are destructive but still chooses to smoke will feel discomfort and revise their attitudes to resolve this tension (ex: convincing themselves that cigarettes are good for stress). Avoiding and resolving bouts of cognitive dissonance can become a motivating force. A doctor who prides herself on being attentive to patients may experience cognitive dissonance if she decides to take on fewer cases to prioritize her energy. A student who views himself as hard-working may experience cognitive dissonance if he decides to take it easy on a group project, and thus cannot help but stretch himself too thin and take control. An employee may have a strong initial conviction that the workplace norms of competition and overworking are wrong. However, over time he may suddenly find himself promoting these norms, and later change his attitudes, concluding that the environment was ruthless and that he had no choice. Due to this strong desire to maintain a consistent view of who we envision ourselves to be—hardworking, dependable, persistent, self-sufficient—we may take on too much and insidiuously adopt unhealthy working behaviors in order to satisfy these beliefs.

References

Bandhu, D., Mohan, M. M., Nittala, N. A. P., Jadhav, P., Bhadauria, A., & Saxena, K. K. (2024). Theories of motivation: A comprehensive analysis of human behavior drivers. Acta Psychologica, 244, 104177.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, October 24). Health Workers Face A Mental Health Crisis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/health-worker-mental-health/index.html

Cherry, K. (2023, August 23). How does drive reduction theory explain human motivation?. Verywell Mind. https://www.verywellmind.com/drive-reduction-theory-2795381

McLeod, S. (2025, March 14). Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/maslow.html

Meyers, D. G. (2004). Psychology (7th ed.).

Leave a comment